“The signatory authority of an examiner may incentivize rejecting claims rather than allowing. Specifically, junior examiners have a greater incentive to reject patent claims and avoid indicating any allowable subject matter.”

The “interview” during the patent prosecution process is a meeting typically held between a patent examiner and the applicant’s representative (i.e., a patent practitioner). In some cases, the inventor, assignee, or a subject matter expert may also be present. During my time as a United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) patent examiner, I would almost always encourage scheduling an interview with applicant’s representative to discuss the merits. Curiously, many patent practitioners are not proactive in initiating an interview with the examiner.

Why is an interview so important? When and how should it be held? How does an applicant’s representative conduct an effective interview?

The Purpose

Interviews can be a powerful tool to shorten prosecution. This is because it gives the applicant a unique insight into how the examiner thinks about their case while also allowing the applicant to convey critical information to the examiner that may be missing or overlooked during the course of prosecution.

When and How to Interview

Interviews can be useful at any stage of prosecution as long as it can resolve issues and help further prosecution. Interviews should be held before prosecution reaches a sticking point. The best time to schedule an interview is usually after the first office action on the merits. In the past, interviews were often held in person on the USPTO campus in Alexandria, VA. Today, however, video conferencing is the most practical way to connect with the examiners, since most examiners work remotely.

The Effective Interview

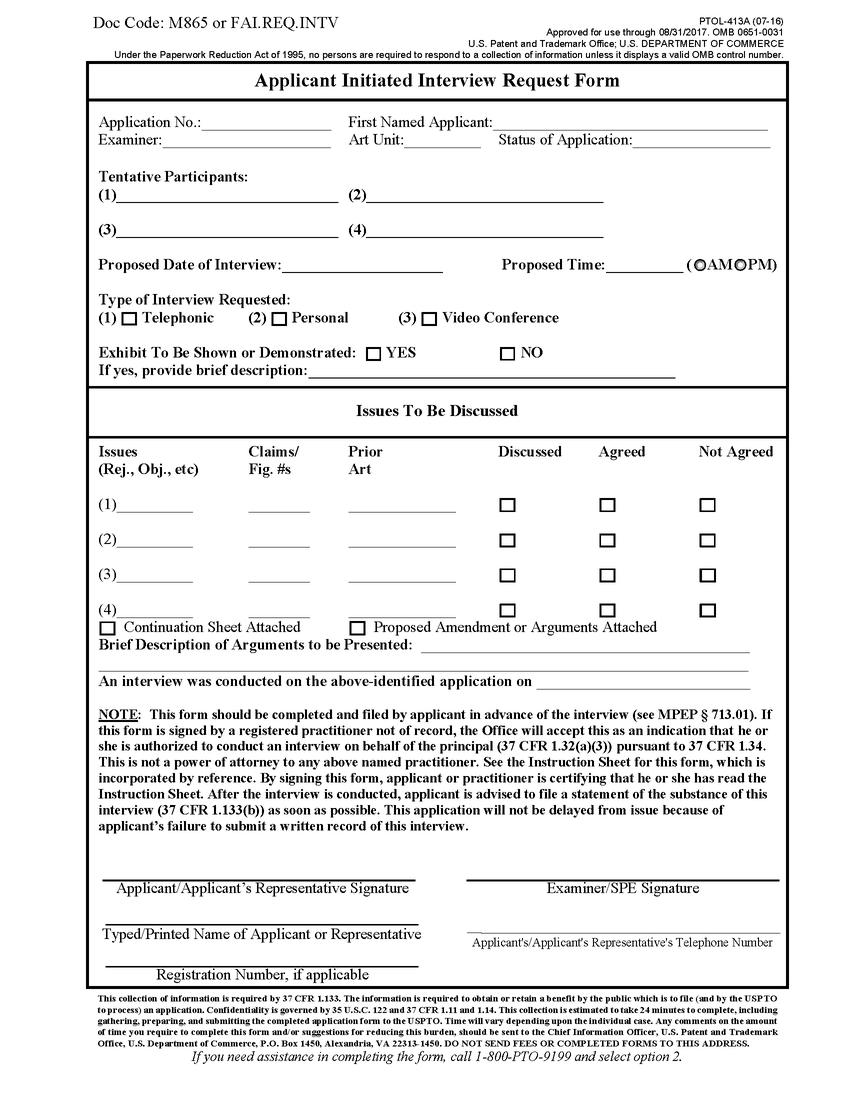

The examiner has a finite amount of time they can spend on a single case. USPTO examiners are only given one hour for the whole interview process, including preparation before the interview and writing the interview summary afterwards. That is why it is very important to conduct an effective interview in as little time as is necessary. The ideal interview lasts no more than 30 minutes. To help the examiner, the applicant or their representative should submit an agenda and any proposed claim amendments at least 24 hours prior to the interview. In addition to facilitating preparation, submitting an agenda can give the examiner time to determine how to approach a favorable outcome based on the proposed strategy proffered by the applicant. After introductions, the actual interview should be short and sweet. Both the examiner and applicant will write up a detailed summary after the interview is over, including whether an agreement was reached.

The Substance of the Interview

After the first office action, the examiner will generally know what the closest prior art is and what it takes to overcome the rejections. Applicant should address each issue and ask if the proposed response would likely overcome the respective objection(s) or rejection(s). However, interviews are not a fishing expedition, and the examiner cannot provide legal advice. Thus, it is up to the applicant to propose their strategy. The practitioner will need to tell the examiner what they think and ask the examiner if that’s something that will advance prosecution and help reach a mutually beneficial outcome. I recommend giving the examiner different strategy options (e.g., different proposed claim amendments). This gives the examiner an opportunity to determine which approach would likely work best. Of course, it also goes without saying that being courteous and respectful to the examiner, especially when disagreements inevitably arise, is crucial to maintaining a good relationship and reaching a favorable outcome. Remember that this examiner will likely see every child or sister patent application related to the invention. Getting on the examiner’s good side early will pay dividends later.

One Versus Two Examiners and Why it Matters

When a USPTO patent application is examined, the Office issues one or more office actions that are either signed by a single examiner or a second examiner with authority to sign. My experience as a former Primary Examiner gave me a unique insight into what this signatory distinction means and why it affects patent prosecution strategy.

Signatory Authority

Not all patent examiners are equal. A USPTO examiner that lacks partial or full signatory authority (typically GS-7 to GS-13) is commonly referred to as a “junior” or “assistant” examiner. After several years of promotions, the certification exam (the USPTO equivalent of the patent bar), and a signatory program where supervisors scrutinize a plethora office actions over a probationary period, an examiner attains the rank of Primary Examiner (GS-14/GS-15) and the authority to sign most office actions. A Supervisory Patent Examiner (“SPE”) is a former Primary Examiner that also has signatory authority along with other managerial duties. SPEs and Primaries approve and sign office actions of junior examiners. The inherent signatory authority of an examiner directly affects decision-making for determining the finality of an application and what can be agreed to during an interview.

Incentives to Reject or Allow

The signatory authority of an examiner may incentivize rejecting claims rather than allowing. Specifically, junior examiners have a greater incentive to reject patent claims and avoid indicating any allowable subject matter. The reason for this is because a junior examiner has the ability to reject patent claims at any point during prosecution, but the determination of allowable subject matter cannot occur without approval from a Primary or SPE. Thus, a Primary or SPE is more likely to accept signing a rejection since that is easier than conferring with the junior examiner for determining allowability. This is especially the case when the junior examiner is under a time crunch to get a case off their docket. Additionally, examiners that have partial signatory authority (“PSA” examiners) have a motivation to reject cases that are non-final since they do not need a Primary or SPE to sign any non-final office actions. In contrast, an allowance is an office action that is final and, therefore, the PSA examiner does require a Primary or SPE to review and sign.

As an example of this phenomenon, in my first three years at the USPTO as a junior examiner, I rarely had a case where an allowance was issued in the first office action, and I rejected claims more frequently than when I became a Primary Examiner. As a Primary Examiner, I could routinely allow cases earlier and often, such as by proactively placing a call to the applicant’s representative to make suggested changes or by issuing an Examiner’s Amendment.

On the other hand, a junior examiner does not have these tools at their disposal and, depending on the grade level, they may not even have authority to conduct an interview without a Primary or SPE present. In theory, it should not make a difference. In reality, however, junior examiners may not be on the same wavelength as their Primary or SPE and issuing rejections is safer and easier to get office actions out the door, even if the grounds of rejection are weak.

Prosecution Strategy Based on Signatory Authority

Each examiner is different, and knowing the signatory authority of an examiner may affect prosecution strategy for the applicant.

It is important to remember that a Primary Examiner is the exclusive authority until a case is appealed. Calling upon a SPE for assistance or requesting their presence in an interview when a Primary Examiner is the sole person examining a case is not only unhelpful but also risks anger and resentment from both the Primary and the SPE. A SPE may automatically presume the attorney is trying to subvert the Primary Examiner’s authority. Challenging a Primary Examiner’s authority to make decisions defeats the whole point of the years and hard work to achieve that title and rank.

On the other hand, requesting a Primary Examiner or a SPE when a junior examiner is being interviewed can be helpful since allowable subject matter cannot be determined without their approval. Moreover, a SPE or Primary Examiner typically has more experience that can facilitate decision making.

The examiner’s signatory authority may affect the strategy to provide claim amendment(s) or arguments. For example, Primary Examiners may indicate how to overcome a rejection in an office action by suggesting a claim amendment. A junior examiner is less likely to reveal what could overcome the rejection. Furthermore, a junior examiner may have a higher likelihood of rejecting claims that are amended, which may not be worthwhile in the first place if the grounds of the rejection are weak.

Finally, the examiner’s signatory authority may also influence the decision as to whether to appeal or continue prosecution. For example, knowing the proclivity of a junior examiner to reject claims adds weight to appealing a case that is ripe rather than filing a request for continued examination.

Each USPTO office action presents one or more issues that need to be resolved when formulating a response. Therefore, knowing the significance of an examiner’s signatory authority can be helpful when addressing those issues.

The Goal: A Roadmap to Allowance

If the applicant or their representative sees at least some benefit, conducting an effective interview can expedite prosecution and minimize costs. Done correctly, the interview should provide the applicant further insight into how the examiner thinks and a clearer roadmap for getting the claims allowed.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Image ID:20780069

Copyright:pincasso