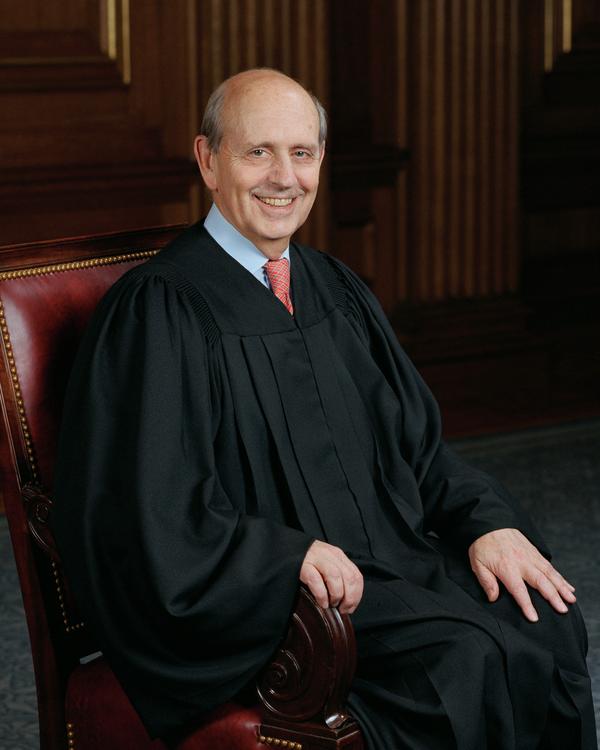

As Justice Stephen Breyer prepares to step down from the Supreme Court later this year, legal experts are highlighting a lesser-known piece of his legacy — an impact on clean energy and electricity markets.

Yesterday, President Biden formally announced Breyer’s plans to retire at the end of this court term during an event at the White House. The 83-year-old justice has served for 28 years on the high court, and four decades as a federal judge (Greenwire, Jan. 27).

Breyer, who came to the court with expertise in natural gas regulation, has been a part of key federal court rulings that have defined how the federal and state energy regulators balance authority over wholesale markets.

The rulings, while not directly related to the transition to a greener energy grid, nonetheless have helped the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and states to proceed with clean energy initiatives and climate targets, experts said.

“Breyer opened the door to a practical view of FERC’s jurisdiction that is adaptable to new technologies and is not fixed by the industry structure that existed when Congress passed the [Federal Power Act] in 1935,” said Ari Peskoe, director of the Electricity Law Initiative at Harvard Law School, in an email.

Energy law experts pointed to one of Breyer’s opinions in 2015 in particular — Oneok Inc. v. Learjet Inc. — as laying the foundation for clarifying that balance of state and federal power under federal law.

One of the enduring parts of Breyer’s Oneok opinion was a test he devised to allow states to play a role along with FERC over wholesale rates, said Jim Rossi, a professor at Vanderbilt Law School.

The key question was whether a state action to enforce market norms “aims at” wholesale rates. Under Breyer’s test, as long as states aren’t interfering with those rates, they can have authority alongside the federal government, said Rossi.

“A lot of the big debates that are going on today find their seed in that ‘aims at’ test that Breyer first articulated in Oneok,” he added.

Those include the extent to which FERC’s regulation of wholesale markets preempts renewable portfolio standards, renewable energy subsidies or zero-emissions credits for nuclear power.

3 cases that shaped FERC

The Oneok case was brought to the Supreme Court by Learjet in 2014. The company argued that Oneok and other energy trading companies had violated state antitrust laws by allegedly reporting false information to natural gas indices, resulting in higher wholesale and retail gas prices.

The question before the court was whether the Natural Gas Act barred these types of challenges as the changed indices affected both federally regulated wholesale natural gas prices and retail natural gas prices controlled by states.

Breyer, along with six other justices, found that the Natural Gas Act didn’t block such legal challenges even though these claims would affect rates set under the federal law, said Carolyn Elefant, a former FERC attorney.

In his opinion, Breyer noted that the challengers and dissenting justices had made the argument that “there is, or should be a clear division between areas of state and federal authority in natural-gas regulation.”

“But that Platonic ideal does not describe the natural gas regulatory world,” Breyer wrote.

The opinion “is a good example of his recognition that an agency, like FERC, does not have the capacity or resources to regulate every transaction on its own under the Natural Gas Act,” said Rossi.

Peskoe said the 7-2 ruling in April 2015 marked the first of a “FERC trilogy” that the Supreme Court ruled on in a one-year time span.

The decision set the stage for the high court’s subsequent 6-2 decision in FERC v. Electric Power Supply Association (EPSA) in January 2016.

In that case, the court upheld FERC’s authority to regulate demand response — in which consumers reduce electricity use in response to high prices — even if it could substantially affect retail sales.

While power generators had argued that that type of regulation was barred under the Federal Power Act, the majority on the court, including Breyer, disagreed.

The court instead ruled that as long as a transaction was done through a wholesale tariff, the effects on retail sales controlled by states did not affect jurisdiction over the case.

The decision “upheld FERC’s demand response rules as a ‘program of cooperative federalism,'” said Rossi.

The final FERC case of the trio was an 8-0 decision in Hughes v. Talen Energy Marketing LLC in April 2016.

In that case, the justices applied Breyer’s “aims at” test to determine that Maryland’s subsidization of wholesale power contracts for natural gas encroached on FERC’s regulatory authority.

“The Court’s holdings in those cases establish a division of authority between states and FERC that might plausibly endure for decades,” Peskoe said.

That includes questions about clean energy incentives and state subsidies in capacity markets.

The rulings have had an impact on the kind of rules FERC has crafted to enhance the adoption of clean energy, said Peskoe. The EPSA ruling, which also built on Breyer’s earlier Oneok opinion, clarified FERC’s role in regulating new technologies, he added.

EPSA helped make it possible for FERC to issue Order No. 841, which allows electric storage technologies to participate in wholesale power markets overseen by regional grid organizations.

It also helped enable Order No. 2222, which similarly required regional grid operators to open their markets to distributed energy resources, such as rooftop solar, electric vehicles, energy efficiency and more (Energywire, Sept. 18, 2020).

Implementation of the latter rule will continue to be litigated at FERC and in federal courts, since existing state regulation of distributed energy resources is pervasive, Rossi noted.

“I also think that there is enough inconsistency in how lower courts have addressed preemption issues after Hughes to date that the issue could well end up before the Supreme Court again in the future,” he added.

That could mean Biden’s pick to replace Breyer could have the opportunity to weigh in on the balance of power in the future.

Pipelines, books and pragmatism

Breyer’s impact on energy market regulation began well before he became a judge.

As a scholar on administrative law in 1974, he co-authored the book “Energy Regulation by the Federal Power Commission” with Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist Paul MacAvoy, which contemplated the benefits of deregulating natural gas by FERC’s precursor.

The book has been credited with influencing the federal regulatory approach laid out in the 1978 Natural Gas Act.

Breyer also tackled FERC’s regulation of wholesale rates while he served as the chief judge on the 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, including one 1990 case, Town of Concord, Mass., v. Boston Edison Co.

Breyer may not have been a great environmental champion, but instead has been a pragmatist as a federal jurist, experts said.

Other examples include his votes alongside the conservative majority to grant approval for the Atlantic Coast pipeline to cross the Appalachian Trail, and for the PennEast pipeline to seize state-controlled land in New Jersey.

“I think he can be characterized as taking a pragmatic approach in these cases, recognizing that finding for the petitioners in PennEast or rejecting Atlantic Coast’s challenge could potentially interfere with energy development,” said Elefant.

Biden noted in his remarks at the White House that during his confirmation to the Supreme Court, he had stated, “The law must work for the people.”

“His understanding of energy … it’s iconic, and it stands out among the existing Supreme Court justices,” said Rossi. “I don’t think any of them have the same understanding the Breyer does, having spent his whole life as a student of economic regulation.”

Reporter Miranda Willson contributed.